Temperature measurements are indispensable in chemical process engineering. They allow reaction progress to be described with high spatial and temporal resolution. Conventional measurement methods quickly reach their limits when electromagnetic immunity, high sensor density, or chemically aggressive environments are required. Minimally invasive fiber-optic sensing offers possibilities that far surpass traditional methods.

Fiber-optic sensing

Glass fiber-based sensors have been used for many years to measure temperature or strain. They offer significant advantages over electrical sensors in environments with strong electromagnetic fields, challenging chemical conditions, or applications requiring high sensor density, long measurement distances, compact size, or low weight.

Conceptually, these fiber-based systems consist of a readout unit and a connected passive sensor fiber. The readout unit sends light into the fiber and analyzes reflected or backscattered signals. Systems are classified as either point-based or distributed. Point-based solutions use a single sensor at the fiber end, or a limited number of fiber Bragg gratings written at predefined positions along the fiber. Each grating acts as an individual sensor.

In distributed measurement systems, there is no need to embed sensors into the fiber. Instead, the light scattered back by the fiber material itself is analyzed to obtain the desired information about temperature or strain. Here, too, two types are distinguished, each preferred depending on the application: systems based on the Raman or Brillouin effect are suitable for measurement lengths of up to several tens of kilometers, with a spatial resolution along the fiber of up to 10 cm.

The second group consists of systems that analyze Rayleigh scattering and allow measurement lengths of up to 50 m with millimeter-range resolution. This way, practically every point of the optical fiber becomes a sensor. Conventional methods would require hundreds or even thousands of conventional point sensors with associated wiring and immense installation effort.

Application in chemical process engineering

In the field of chemical process engineering, distributed fiber-optic temperature measurement is becoming increasingly widespread. Knowledge of temperature profiles along a cooling or reaction path allows for better process control and provides valuable insights for optimizing plant geometry. The high measurement point density of distributed systems enables, for the first time, a quantitative comparison with existing FEM models and improves the understanding of ongoing processes. Three practical examples from process engineering illustrate the advantages of this application.

Optimization of condensation processes

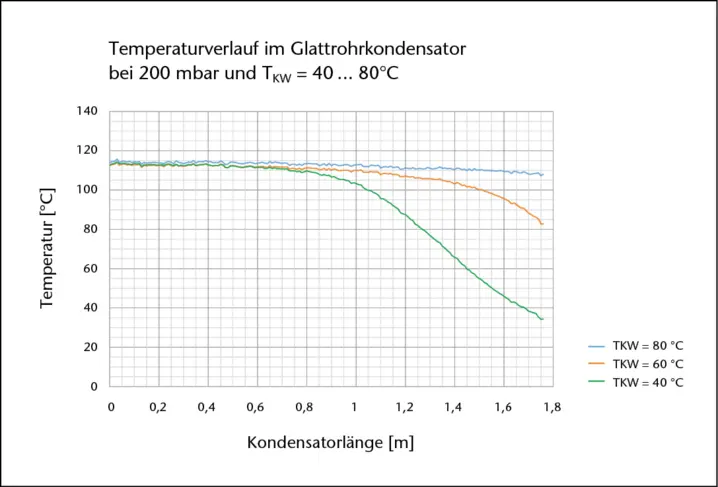

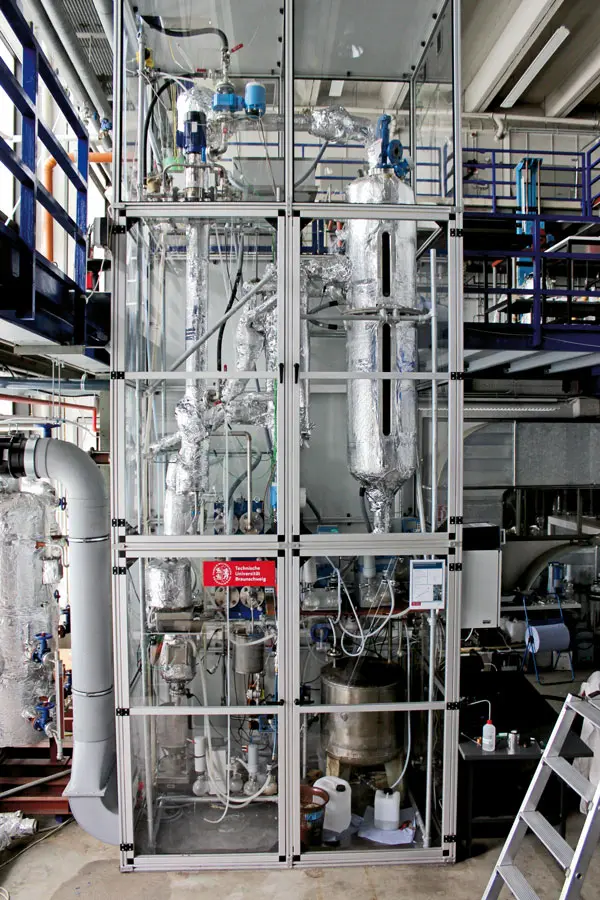

At TU Braunschweig, in collaboration with the British company CalGavin Ltd., Alcester, investigations were carried out on heat transfer and pressure drop in a 2-meter-high condensation reactor (smooth-tube apparatus) using hexanol condensation as an example. The condensation behavior in the reactor tubes is largely influenced by the design of the cooling system. In several tubes, a capillary-guided optical fiber was installed along the entire length of the condenser. This installation is minimally invasive, so its impact on flow conditions is negligible. The measured temperature profiles and their temporal evolution describe the condensation behavior very accurately, both when varying the reactor geometry and when changing operating parameters such as pressure or the amount of hexanol at the condenser inlet.

The temperature profiles were determined using the distributed measurement system ODiSI-A with a spatial resolution of 1 mm. The figure at the bottom left illustrates the influence of the cooling water temperature (T_CW) on the condensation point in the reactor. In all temperature profiles, the measured temperature at the beginning of condensation is constant. From a length of approximately 0.8 m, condensation is almost complete at a cooling water inlet temperature of 40°C. Beyond this point, only the gas flow in the center of the tube is cooled, which is reflected in the temperature drop. At a cooling water inlet temperature of 60°C, this “kink” occurs noticeably later, and at 80°C it is no longer observed.

This means that at 80°C, the condenser is no longer able to fully condense the incoming hexanol vapor. This insight is crucial for optimizing plant and operating parameters and ultimately contributes to increasing the material throughput.

Investigation in a natural circulation evaporator

The University of the Bundeswehr in Hamburg used an ODiSI system for measurements in a natural circulation evaporator. Evaporators are widely used in the chemical industry as sump heaters for distillation columns and in steam power plants. They operate without pumps, as the circulation flow is generated by partial vaporization of the mass flow.

Local heat transfer and flow phenomena were investigated under variation of the operating parameters, followed by model development. For this purpose, the method of high spatial-resolution fiber-optic temperature measurement was used, among others. A better understanding of the interactions is intended to stabilize the overall process, increase material throughput, and thus reduce operating costs.

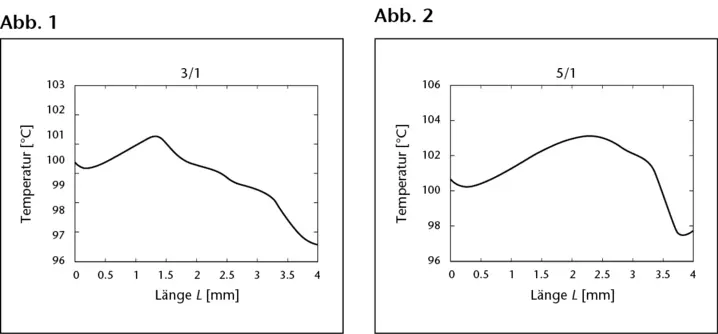

The heart of the evaporator consists of a vertically arranged tube bundle with walls that can be heated in a controlled manner. A 4-meter-long capillary-guided sensor fiber was installed in one of the tubes, reaching down to the sump of the evaporator. The stainless-steel capillary, with an outer diameter of 0.8 mm, is minimally invasive to the flow. It is also chemically inert and can withstand pressures well above 100 bar. Since temperatures of 550°C and higher can be reliably measured in principle, the measurement setup is also well suited for other types of tubular reactors.

Figures 1 and 2 show the temperature profile from the upper steam outlet down to the condensate inlet located 4 m below. At a constant operating pressure of the process fluid of 1 bar, the pressure of the heating steam was varied between 2 and 5 bar. A spatial shift of the maximum in the temperature profile was observed. The spatial resolution of the measurement was 5 mm. The pressure at the outlet of 1 bar corresponds very well to the measured 100°C (boiling point of water). Toward the inlet, the pressure increases to approximately 1.4 bar, which corresponds to a local decrease in temperature of 3 to 4°C. This is confirmed by the distributed temperature measurement.

Cooling system investigations in nuclear reactors

The PANDA facility at the Swiss Paul Scherrer Institute (cover image) is a large thermohydraulic test facility for investigations on the safety of nuclear reactor containment systems as well as various advanced light-water reactor designs. The facility examines cooling systems for passive radioactive decay heat and the behavior of containment vessels of simple boiling water reactors under accident conditions. PANDA is modular in design, allowing the behavior of pressure vessels, water pools, or condensers to be simulated and systematically studied for different applications.

The total volume of the vessels is approximately 460 m³, with a height of up to 25 m. Maximum operating conditions are 10 bar and 200°C. Air, helium, and water can be injected into the vessels, as well as steam, which is heated up to 1.5 MW. This allows the test environment to be adjusted to the specified conditions. For spatially resolved temperature measurement, a sensor fiber in a stainless-steel capillary was installed horizontally through the lower part of a pressure vessel above a core spray ring.

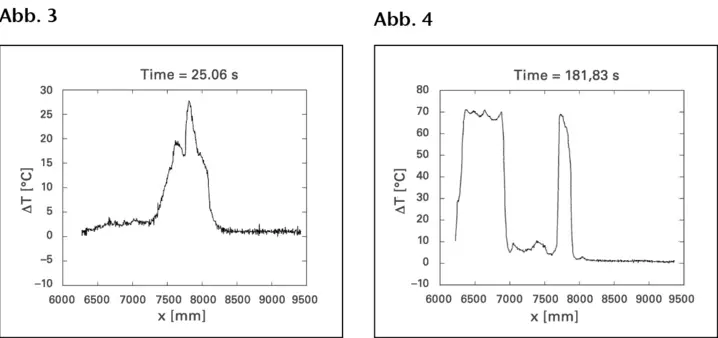

In various investigations, hot air and steam were injected at rates between 15 and 50 g/s. Figure 3 shows, as an example, the radial temperature distribution in the vessel, with two temperature maxima. After the removal of the core spray ring, the temperature distribution across the vessel cross-section appears significantly different due to the altered flow patterns (Figure 4).

Previous measurements were carried out using approximately 300 thermocouples and were much less informative due to the lower measurement point density. Using fiber-optic measurements, far more meaningful results could be obtained in a shorter time with considerably less installation effort.

Conclusion

Fiber-optic sensor systems open up possibilities for process engineering—particularly in the field of temperature measurement—that go far beyond conventional methods. Their independence from electromagnetic fields, chemically aggressive environments, and confined spaces, as well as their time-saving implementation, ease of use, and long-term durability, are highly promising. Practical application examples demonstrate that this mature technology delivers on its promises.

Polytec has been established as an expert in optical measurement technology for over 50 years. With its extensive experience in industrial and research projects, the company offers manufacturer-independent consulting expertise that encompasses all commercially available technologies.