Since the 1960s, sterile packaging has played a crucial role in food safety. Yet, since then, there have been few innovations. Chemicals and heat remain the most common methods for sterilizing food packaging—just as decades ago. This may finally change, as pulsed light has proven to be a highly effective and energy-efficient alternative with many applications.

Sterile packaging means disinfecting the packaging separately from the product, then sealing it as quickly as possible under sterile conditions. Benefits include preventing contamination, reducing refrigeration needs, extending shelf life, and preserving taste and nutritional value.

However important this process is, the techniques used are old—with limitations in both application and effectiveness. For example, chemical treatments with chlorine, peracetic acid, or hydrogen peroxide are effective but can leave residues that cause allergic reactions or illnesses, especially if they enter the product. Many chemicals also require special and costly disposal.

Heat treatments using steam, hot water, or air are often combined with chemicals. While they can kill bacteria on various packaging materials, energy costs are high. Heat can also damage packaging materials or reduce their functionality.

Other sterilization methods include retort processing and packaging under modified atmosphere. But like chemical and heat treatments, these can affect packaging materials and are expensive to implement and maintain.

The Alternative: Pulsed Light

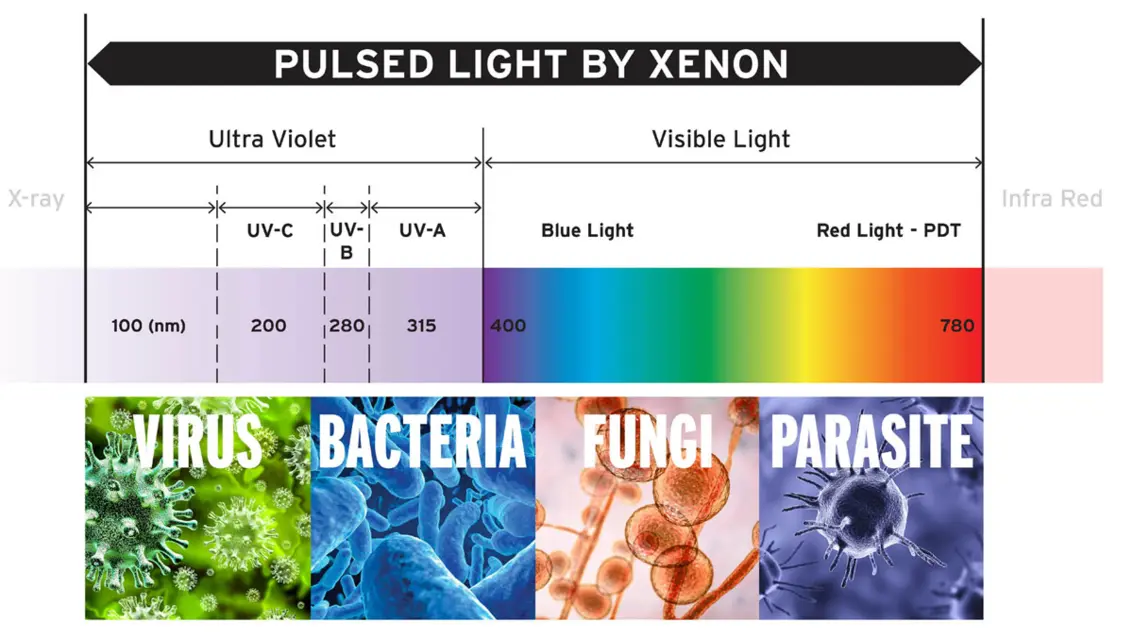

Pulsed light consists of a series of intense UV-C flashes that deliver high energy with minimal heat. Essentially, it harnesses concentrated sunlight in the form of high-power pulses of several megawatts.

Pulsed light differs greatly from low-energy UV light used in dermatology and some consumer applications, as it is orders of magnitude more effective.

It is highly efficient at killing pathogens by acting on the DNA level, deactivating enzymes, and destroying nucleic acids. Additionally, it works within seconds and is free of chemicals and gases.

Since it produces no byproducts and does not affect packaging properties, it can be adapted to many production environments.

In fact, this technology is FDA-approved for food use, allowing safe application even after packaging without affecting the food itself.

A typical use is disinfecting yogurt cups immediately before filling (see cover image).

What Research Shows

Pulsed light has proven effective in numerous studies at destroying pathogens. For example, Pennsylvania State University conducted extensive research confirming its efficacy—including a study demonstrating that pulsed light can safely disinfect eggshells. Researchers at Cornell University in New York have also investigated pulsed light in relation to food packaging.

Led by Dr. Carmen Moraru, Professor of Food Science, their research shows promising results. In multiple experiments, pulsed light rapidly destroyed resilient pathogens like Listeria and E. coli without compromising food quality. Moreover, microorganisms repeatedly exposed to pulsed light did not develop resistance.

What Does a Pulsed-Light System Include?

A typical pulsed-light system consists of one or more flash lamps, a power supply, an air-cooled housing, and controllers. A standard power outlet is sufficient to meet the energy needs of a basic system.

Effectiveness depends on direct exposure to the special lamps. In other words, it works on surfaces directly exposed to the light. To ensure complete exposure, flash lamps must have the correct working distance, angle of incidence, energy, and timing for the application.

Because every food package is different, testing is necessary to find the optimal setup. Polytec offers SteriPulse systems in various lamp sizes and shapes, making it easy to integrate them into diverse packaging applications.

Pulsed Light in Production Environments

One major advantage of pulsed light is that it can be used virtually anywhere in the process of food production and packaging — even with materials and food products for which other sterilization techniques are not suitable.

Thus, pulsed light can serve as an additional measure in combination with other techniques, as a replacement for less effective processes, or as a completely new method. For example, pulsed light can be applied during the conventional pre-filling phase, but also inline for continuous sterilization during and after the packaging process.

Once a system has been installed, it operates with lower maintenance requirements and reduced energy consumption compared to chemical or thermal methods.

Pulsed light can also be applied in other areas of food processing, for instance, for continuous sterilization on conveyor systems. It is even used for disinfecting floors and ventilation systems. Almost any food safety system can be enhanced with a pulsed light system as an additional safeguard.

The lamps operate with high efficiency, using less energy than conventional disinfection methods. Cooling ensures dairy products don’t heat up during disinfection, and the stainless steel, washable lamp housing can be easily cleaned with steam if needed. The system is user-friendly and simple to operate, reducing operational complexity. Users avoid waste disposal, chemical handling, and chemical residues altogether.

Conclusion

New technologies are part of the solution for preventing foodborne illnesses. Pulsed light is one such technology.

To be effective in food safety, such a system must deliver consistent performance. Both research and current industrial applications demonstrate that pulsed light technology is safe, efficient, versatile, and significantly more environmentally friendly than conventional methods.