Friction clutches are used in millions of automobiles to transfer the engine’s torque to the drivetrain. However, to this day, the physical processes involved in frictional power transmission are not completely understood. This is reason enough for the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) to take a closer look at the friction process.

Temperature is a crucial measurement parameter in many technical and scientific questions. On one hand, it serves process control purposes, and on the other, it often provides insights into the underlying mechanisms. Modern fiber-optic sensor systems enable temperature measurements not only at single points but also with a high spatial density in the millimeter range along the entire length of an optical fiber.

At the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), the Institute of Product Engineering (IPEK) has succeeded, with the help of this technology, in gaining a more detailed understanding of the thermomechanical behavior of friction clutches. According to the Karlsruhe researchers led by Professor Albert Albers, the description of the main function of a dry-running friction clutch—namely the frictional transmission of torque and rotational speed—is still the subject of ongoing research. The understanding of the underlying processes in tribological contact (tribology from Greek: the study of friction) is incomplete, although it is of great importance for the development of new products.

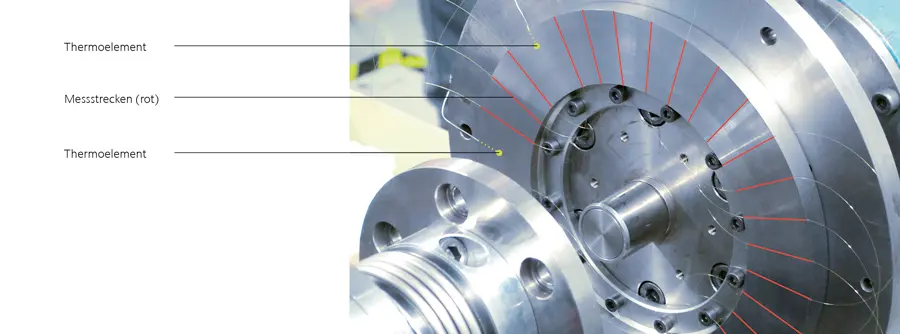

To make progress in this area, a specially designed test setup was developed and examined on the advanced dry friction test rig at IPEK. By using the fiber-optic measurement system, temperature distributions very close to the friction contact were captured with a spatial resolution of 1.25 millimeters. Image 3 shows how the 155-micrometer-thin optical fiber was integrated into the counter friction disc of the system, allowing more than 700 measurement points to be recorded with a single sensor fiber. The fiber was guided in ultra-thin boreholes just below the friction surface in 28 radial segments. Additionally, four conventional thermocouples were installed as references, which showed good agreement at the respective measurement points. For understanding the dynamic behavior, it was crucial to read out all measurement points in parallel with the used readout unit (Luna ODISI B) at a sampling rate of 23 Hertz.

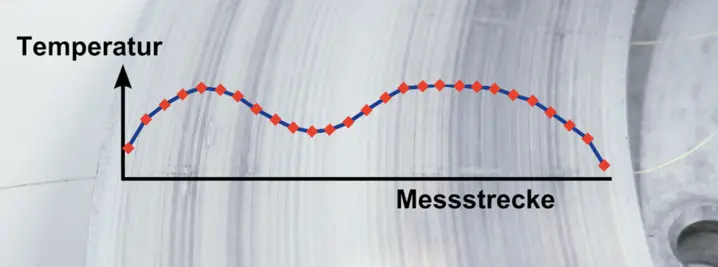

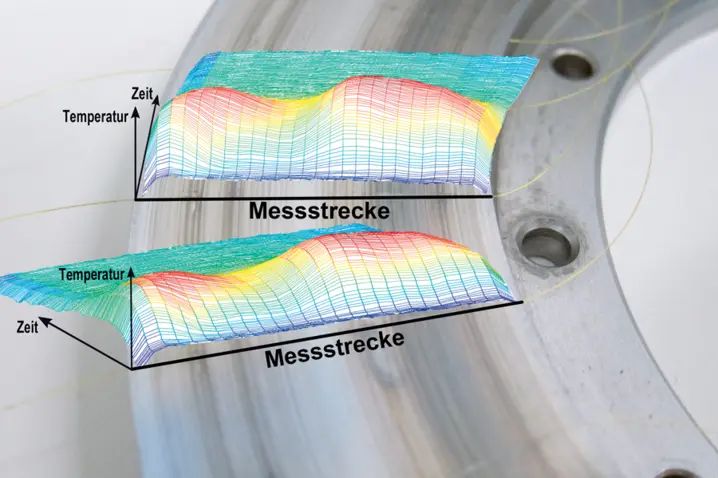

To analyze the friction behavior under various realistic load conditions, the parameters of initial rotational speed (from 500 to 2,000 revolutions per minute) and contact pressure (0.09 to 0.2 newtons per square millimeter) were varied in braking tests. During the runs, the temperature behavior of the entire measurement field was monitored and recorded spatially and temporally. Figure 1 shows, as an example, the temperature profile along a radial measurement section at a fixed point in time corresponding to the maximum temperature increase. Two temperature maxima develop, which also correspond to the resulting friction marks. Figure 2 documents the complete spatiotemporal behavior at two consecutive measurement segments. It can be seen how the two maxima develop over time from an initially uniform distribution.

Since the temperature development in these experiments could be documented over the entire surface of the friction disc—not just at a few points as with thermocouples—a detailed analysis of the thermomechanical behavior is now possible. The system behavior is linked to the test parameters of contact pressure, sliding speed, mass inertia, and the resulting slip time. From the analysis of the complete set of parameters, targeted optimization measures for the examined friction system can now be derived.

One goal could be to homogenize the temperature distribution in the counter friction disc. This would increase the overall system’s load capacity. Furthermore, the system can be adapted to its operating range, or the influence of various load parameters such as friction energy or power can be analyzed.